Python’s __slots__ is a simple yet powerful feature that is often overlooked and misunderstood by many.

By default, Python stores instance attributes in a dictionary called __dict__ that belongs to the instance itself.

This common approach is associated with significant overhead.

However, this behavior can be altered by defining a class attribute called __slots__.

When __slots__ is defined, Python uses an alternative storage model for instance attributes: the attributes are stored in a hidden array of references, which consumes significantly less memory than a dictionary.

The __slots__ attribute itself is a sequence of the instance attribute names. It must be present at the time of class declaration; adding or modifying it later has no effect.

Attributes listed in __slots__ behave just as if they were listed in __dict__ - there’s no difference.

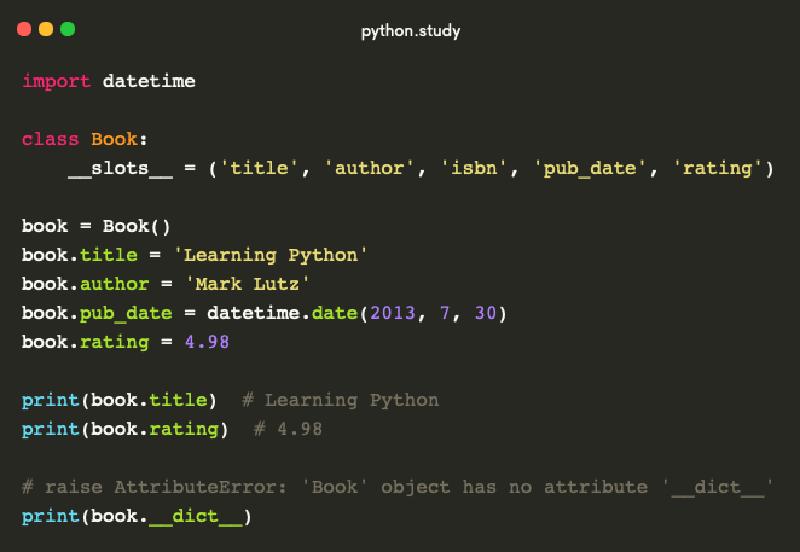

However, __dict__ is no longer used and attempting to access it will result in an error:

import datetime

class Book:

__slots__ = ('title', 'author', 'isbn', 'pub_date', 'rating')

book = Book()

book.title = 'Learning Python'

book.author = 'Mark Lutz'

book.pub_date = datetime.date(2013, 7, 30)

book.rating = 4.98

print(book.title) # Learning Python

print(book.rating) # 4.98

# This will raise AttributeError: 'Book' object has no attribute '__dict__'

print(book.__dict__)

So, what are the benefits of using __slots__ over the traditional __dict__?

There are three main aspects:

I. Faster access to instance attributes

This might be hard to notice in practice, but it is indeed the case.

II. Memory savings

This is probably the main argument for using __slots__.

We save memory because we are not storing instance attributes in a hash table (__dict__), thus avoiding the additional overhead associated with using a hash table.

This can be easily verified in practice using the Pympler library:

from pympler import asizeof

class Point:

def __init__(self, x: float, y: float):

self.x = x

self.y = y

class SlotPoint:

__slots__ = ('x', 'y')

def __init__(self, x: float, y: float):

self.x = x

self.y = y

p = [Point(n, n+1) for n in range(1000)]

print(f'Point: {asizeof.asizeof(p)} bytes') # Point: 216768 bytes

p = [SlotPoint(n, n+1) for n in range(1000)]

print(f'SlotPoint: {asizeof.asizeof(p)} bytes') # SlotPoint: 112656 bytes

In our example, the memory savings were almost twofold. However, the savings will not be as significant if the object has more attributes or if their types are complex. The savings might only amount to a few percent.

III. More secure access to instance attributes

__dict__ allows us to define new attributes on the fly and use them.

__slots__ restricts us to what is listed in it:

class Book:

pass

class SlotBook:

__slots__ = ()

book = Book()

book.title = 'Learning Python' # no error, a new attribute is created

print(book.title) # Learning Python

book = SlotBook()

# This will raise AttributeError: 'SlotBook' object has no attribute 'title'

book.title = 'Learning Python'

Whether to use __slots__ or not depends on the specific case.

It might be beneficial in some cases and problematic in others, especially in more complex scenarios, like when inheriting from a class that has defined __slots__.

In this case, the interpreter ignores the inherited __slots__ attribute, and __dict__ reappears in the subclass:

class SlotBook:

__slots__ = ()

class Book(SlotBook):

pass

book = Book()

book.title = 'Learning Python' # no error, a new attribute is created

print(book.title) # Learning Python

But don’t be afraid or forget about __slots__.

Use it in simple cases where there is no inheritance, few attributes, and the attributes are simple types, like numbers, especially when the number of your instances is in the hundreds of thousands or millions.

At the very least, you’ll get a noticeable memory saving.

For more detailed information about __slots__, you can refer to this great article: Using Slots.